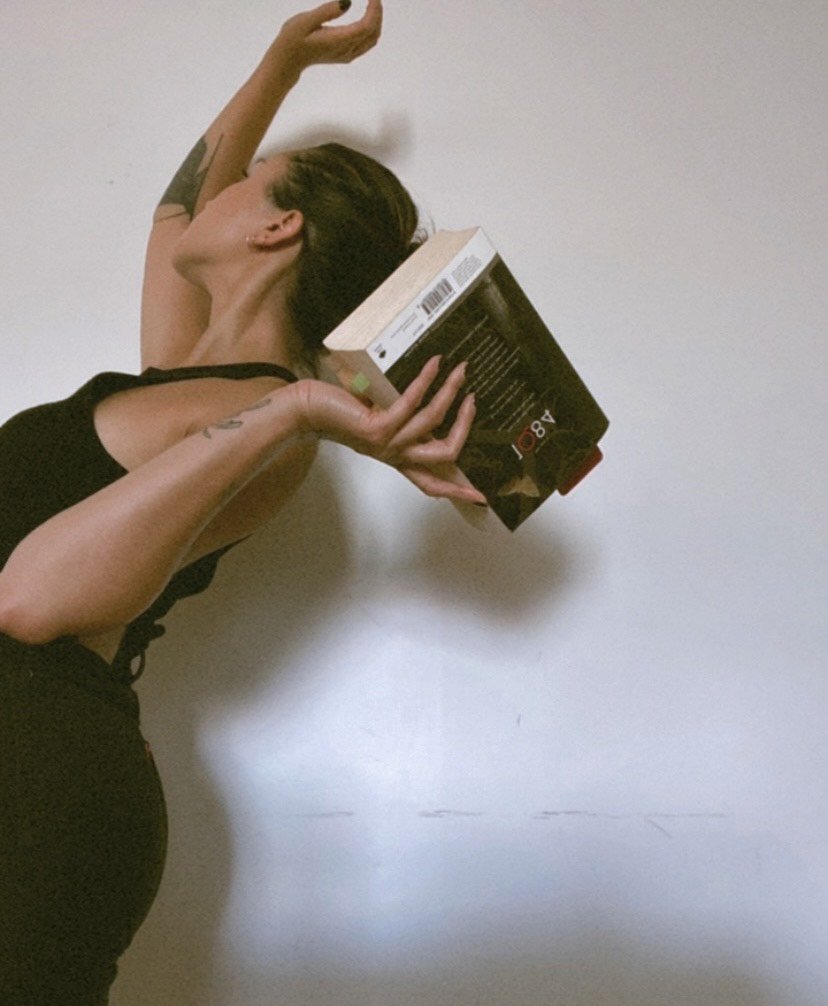

Book Review: What I Loved by Siri Hustvedt

RACHEL SOO THOW - 19 APR 2022

“Every story we tell about ourselves can only be told in the past tense. It winds backward from where we now stand, no longer the actors in the story but its spectators who have chosen to speak. The trail behind us is sometimes marked by stones like the ones Hansel first left behind him. Other times, the path is gone, because the birds flew down and ate up all the crumbs at sunrise. The story flies over the blanks, filling them in with the hypotaxis of an “and” or an “and then”. I’ve done it in these pages to stay on a path I know is interrupted by shallow pits and several deep holes. Writing is a way to trace my hunger, and hunger is nothing if not a void.”

Boy oh boy, am I in love with this novel. I knew that with this being a Hustvedt, there was no going back – it was going to be riveting, intricate, deep and romantically fragile and I wanted to take my time with this in order to become fully immersed in the pains and joys of it all. I had previously read Hustvedt’s essay collection, ‘Living, Thinking, Looking’ and her prose just had me absolutely floored- there’s a certain effortless clarity her writing provokes that will leave you feeling as though your personal identity has been ripped open with such consummate intensity.

But back to this novel - this is the story of two men (Leo and Bill) who become friends in 1970s New York and it becomes inevitable that their wives and sons of the same age would become intertwined over the coming years. Tragedy beholds the family and the plot becomes dotted with satisfying and sensical prose in typical Hustvedt fashion; every page was memorable and finishing each chapter was like waking up from a dream still dense in intellect and ambition. The novel is told by narrator Leo Hertzverg ( a professor of art history), and as he looks back on his life in old age, his retelling is stunning. There are detailed descriptions of Bill’s art as well as consistently perceptive and intriguing ‘studies’ of pieces of art such as Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’-

“ … the loose energy of his lines and his fierce rendering affected me like an aphrodisiac. I kept turning the pages, eager for more pictures of brutes and monsters. I knew every one of them by heart, but that night their carnal fury scorched my mind like a fire, and when I looked again at the drawing of a young, naked woman riding a goat on a witches’ Sabbath, I felt that she was all speed and hunger, that her crazed ride, born of Goya’s sure, swift hand, was ink bruising paper. His beast runs, but his rider is out of control. Her head has fallen back. Her hair streams out behind her and her legs may not cling much longer to the animal’s body. I touched the woman’s shaded thigh and pale knee, and the gesture sent me to Paris.”

What I loved after listening to Hustvedt’s interview on this book in the BBC World Service ‘World of Books’ podcast was that she likened these acute references to graphic novels and comics: whilst the action happens in a box, she chose to take on this idea and play with the idea of the frame, an aesthetic frame. Hearing Hustvedt’s voice was absolutely magical and I’d liken it to David Attenborough – it was like being led on a journey and being read a novel with dreamy harps playing in the background (if you get a chance to experience listening to Hustvedt, I would highly recommend it!). Hustvedt has this way of demonstrating a certain kind of catharsis about living with tragedy and experiencing it, and that in some perverse way, we like it – it deepens our human experiences and leads to a sort of protection of our being. Hustvedt chose to play on this necessity with such force that we are thrust into it - alarmed at this rare feat of emotion and pain yet enabled with the choice of walking away. With Hustvedt, grief becomes psychologically overwhelming and psychopathy and emotional deficits seem to weave in and out of this saga.

“… I cried in front of a woman I didn’t know at all. After I left her, I wiped my face in her small neat bathroom with its bountiful supply of Kleenex and imagined all the people who had been there before me, wiping away their tears and snot beside the toilet. When I walked outside the building on Central Park West, I looked across at the trees that had burst into full leaf and had a sensation of ineffable strangeness. Being alive is inexplicable, I thought. Consciousness itself is inexplicable. There is nothing ordinary in the world.”

I grew with these characters and I wept with these characters. The icons of the past and the present are merged in the simultaneity of the art world and family dynamics. We are immersed in brutal dimensions and frightening truths and Hustvedt successfully illustrates these through the conscious and the unconscious. A mute dialogue exists between the reader and the hallucinatory reality of the narrative - this natural magic is consuming, sinister and attractive. A definite must read and an easy five stars.

![[Friday Feature] Valere: Interview & Review of Single/Video ‘Lily’s March’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1712873492906-GFSK6SW4FJ2Z2STOJVAM/Valere+-+Photo+Credit+Hayden+Graham+%281%29.jpg)

![[Video Premiere] Sig Wilder & Friends: Video for ‘Texasman’ + Interview](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1699397388451-3GDFG0FOA5T5WPA33ANE/IMG_2393.JPG)

![[International] Jackson VanHorn Releases New EP ‘Liminal Music, Vol. 1’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1695708847770-UF5H8G2X7N9Q9KF22TA5/Jackson+VanHorn+Liminal+Music+Vol+1.jpeg)

![[Friday Feature] Jazmine Mary: Interview + New Album ‘Dog’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1686280012940-2OBAFHQ9HIJFIVNYE3CZ/JazmineMary_Album+image+no+text+-+Credit+-+Jim+Tannock.jpg)

![[Video Premiere] Emily Rice Releases New Single/Video ‘Warenoa’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1685044212209-9X8UTD0I22FY3LAGKDHI/Press+Shot_+Photo+Credit%2C+Charles+Looker.jpg)

![[Australia] Benny Time: Interview + New Album ‘Benny and Friends’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1653689671831-U73A00Y16B4PYUPIEY7X/Benny+Time+3596.jpg)

![[International] Alison Clancy: Poised for Greatness](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1645751104499-HT5MCDXMERC9SDSW4XW5/Alison+Clancy+Mutant+Gifts+Cover.jpeg)

![[International] Halfway Harbor: ‘Table Stains’](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1644389562677-EPD8X84SUDEW0Y5THAX3/HH+Photo+2.JPG)

![[Video Premiere] Rewind Fields Releases Video for ‘Photographs’ from New Self-Titled Album](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/60df978127837427ee475bb1/1645087328492-XGACSPK0JASK6GHYPNJ8/Rewind+Fields+Press+Photo.jpg)